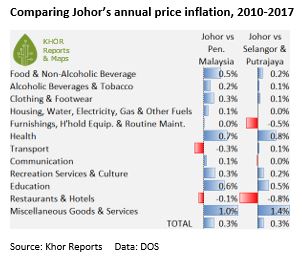

Climbing down from high politics and big business, we have Malaysian voters feeling the pinch of the cost of living amidst relatively stagnant incomes and rising cost of living pressure (Read our Johor case study, examining the cost of living and housing affordability for urban and rural folk; and Bank Negara’s concerns about a living wage). The effect of the GST and the long term weakening of the Malaysian Ringgit does not help, but a pre-election currency appreciation and rising oil prices (while pump prices are carefully kept on hold) help the Najib administration in various ways.

What hope amidst mudslinging?

While there is a litany of criticisms on policy and governance on the long-ruling coalition, the opposition have not been spared complaints. The rumblings against the opposition run states (including anti-corruption allegations in Penang and Selangor) are often defended as politically motivated. The asymmetry of findings on 1MDB-related allegations (multiple foreign prosecutions and asset seizures, plus mega-yacht Equanimity and big headlines in Indonesia versus domestic “no case - no action”) is obvious. It has those in Malaysia (and globally) caught up in similar concerns (but involving lesser alleged amounts) pointing to the US Department of Justice 1MDB case in mitigation.

Given mudslinging across the political spectrum, some urbanites think that it’s not about who will govern better. The more gloomy ask this: “What is the difference?” The optimistic point out that checks and balances are necessary to have a responsible government, and that can only happen if those who govern know they will be held to account. So they refute all those who say that nothing will change, even if they vote for the (tarnished) opposition.

The wags point out that voters should choose the opposition even if there are shortcomings. Then, Malaysians can enjoy having (the alleged governance-challenged) Barisan Nasional as watchdogs, keen to be voted back in the next time. Then vote out the “opposition” if it underperforms, and bring back Barisan Nasional. And so on. But of course, urban intellectuals point out that there also needs to be reform of the Malaysia electoral system.

East Malaysia’s misgivings about “Malaya”

As the Opposition in the Peninsula pressed onwards with criticisms towards the ruling government, the Najib Administration spent 2016 - 2017 negotiating significant governance-related deals with East Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak. Both states have long held misgivings about the Federal Government’s focus on Peninsular Malaysia or “Malaya”, especially with regards to economic development. Due to their large non-Muslim populations there have also been clear misgivings, notably in Sarawak, about PAS’ push for the introduction of hudud. Barisan Nasional is seen as an enabler for the tabling of Hadi Awang’s RUU355 private member bill in Parliament.

In 2017, the Sarawak state government sent a team to review the recently declassified documents pertaining to the Malaysia Act of 1963 (MA63), and returned with findings related to the rights of Sarawak on land and sea matters.

Furthermore, in recent years Sarawak undertook a series of actions to regain control over the lucrative oil and gas industry, including introducing a moratorium on employing non-Sarawakians in Petronas, establishment of Petroleum Sarawak (PETROS), and initiated a takeover full regulatory oversight of upstream and downstream oil and gas operations from Petronas. Sarawak continued to exercise its MA63 rights and pursuit of self-governance through the acquisition of Bakun dam (the largest potential source of hydroelectricity energy in Sarawak with 2,400 MW installed capacity), and the establishment of the Sarawak Development Bank.

Issues in Sabah include security concerns that spilled over from the 2013 standoff between Malaysian security forces and Sulu insurgents in Lahad Datu (early on attributed to a land conflict or misunderstanding and later overtaken by Suluk territorial claims), misgivings about the withholding of rights under the Malaysia Act of 1963, and transportation infrastructure concerns across the state.

While Sarawak’s political class appears very united, Sabah will face a political contest, with the challenge brought by Shafie Apdal’s Sabah Heritage Party (Warisan). A possible voter swing is eyed. This has also been characterised anti-corruption allegations (Shafie called to MACC) and intra-family political rivalry. With a pact (but not a formal alliance), can Warisan bring crucial seat numbers to the Pakatan Harapan challenge for the mandate to rule Malaysia?

Heavy-handed moves amidst expectation of an “easy win”

Polling day is on Wednesday, 9 May 2018. The midweek election is unprecedented and is expected to suppress voter turnout. We are keeping an eye on how up to 3.5 million Malaysian voters get on the road, needing to head back to their hometowns or villages to cast their vote.

The international consensus seems to be for an easy Najib win (with gerrymandering, malapportionment and other tactics), but with more seats for Pakatan Harapan. Some regular urban voters ask if Najib-BN’s recent slew of heavy-handed moves signal that things are worse for BN than they had realised. These include the deregistration of Mahathir’s party that unexpectedly pushed the opposition under one flag. The midweek polling day gave rise to a social media movement (but it has come under cyber attack). Mahathir is being investigated for fake news as he alleged sabotage that grounded his jet on nomination day. His picture is being removed from posters, with new restrictions on campaigning; while Bersih asks about like action against Barisan Nasional figures. Perhaps it is no surprise that so many media outlets across Malaysia are referring to GE14 as “the mother of all elections”.

Assisted by Jeamme Chia.

#Malaysia #PRU14 #GE14 #PoliticalEconomy #NajibRazak #GE14chedet

(c) 2018, Khor Yu Leng. All rights reserved.