Development and water

In contrast to high politics, these issues are in the realm of low politics, and are localised or sub-regional issues. There are cases of resistance to rising urban density, water supply outages and extreme events like major flood crises. Malaysia NGOs typically blame deforestation (land clearing) for unusual flooding, as do various experts. In Thailand’s mega floods, the situation was similar, with the problem blamed on development, bad planning and officials, despite expert ambivalence on causality. What is common in various countries post-flood is a crackdown on logging and deforestation.

In the wake of the 2017 massive floods in Penang and Kedah, the Institution of Engineers Malaysia calls for a new comprehensive planning: "the master plan should include the flood mitigation and prevention action plans, for current and future developments, land use changes as well as climatic change factor."

Selected issues:

In the Klang Valley, Selangor has been beset by water supply issues for over a decade. In some areas, residents worry about the conversion of parks to property projects, including in Taman Rimba Kiara and Taman Desa, congestion problems during peak hours, and over-development.

Social activists points to a Penang (development) Dilemma; and concern about environment-development issues, notably about (real estate) hillslope developments and disgruntled residents. During rainy periods, small landslide risk is of concern. (However, there does not seem to be major risk concern as there is better engineering implementation on Malaysian hillsides.) Amidst local finger-pointing, Penang leaders argue that a freak storm and flood was politicised a few months ago.

Pahang issues include polluting aluminium mining that faced a ban (with exceptions), and an (anti-corruption) seize-and-release case. Earlier, a rare earth processing plant by Lynas of Australia caused concern and is likely to be an ongoing issue given the traumatic history of Mitsubishi's rare earth processing in Perak (with USD100 million voluntarily spent on its clean-up). Logging risks will first immediately affect the water source for villagers, and nature spots like Tasik Chini have been spoilt by various activities.

In Kedah, concerns have arisen on logging and sand mining, and seem to persist. There is concern about its effect on the water supply to the three northern states of Peninsular Malaysia, with some finger pointing between the authorities of Penang and Kedah.

Kelantan’s Orang Asli living near Gua Musang were affected by logging and durian plantation development, also giving rise to some blockades. The flood of 2014 was record setting (bankers tell of the first floor of bank branches entirely engulfed and planters talk of 15-20 meter tall oil palm trees submerged) and triggered by exceptional rain, but experts point to the problem of deforestation.

In Sabah, there is a electoral promise of better wildlife protection.

Fiscal federalism

Stronger state finances are often linked to increased land development (which state administrations fully control). It is regularly noted that Malaysian states rely on revenues from land related activities. Malaysia’s centralised federalism is criticised for a fiscal federalism that needs a fairer and more balanced distribution of revenue collection. At the Federal level, there is notable rising funding to the Prime Minister’s Office, with a large discretionary (development) spending portion and centralised control over even more. Budget experts note that this is often mirrored at the state level, with Chief Ministers having control over large discretionary budgets too, with little to distinguish BN and non-BN run states.

A lawmaker points out that only 2.4% of federal revenue goes back to states. Nevertheless, after the massive flood of 2014, Kelantan has been criticised for over-reliance on funding via concessions and logging. Activists ask its government to find other sources of revenue. Within the bounded context of state finances, it is clear that there is still an expectation that states have better governance and non-land revenues.

Perspectives on development

Land development includes extensification of economic activity with logging and timber plantations depending on the type of forest zones; intensification with forest conversion to agriculture, and agricultural land conversion to non-agriculture; and hyper intensification with upward revised plot ratios for high-density urban landscapes. It also covers large infrastructure projects (E.g. East Coast Rail Link, Pan Borneo Highway) and land reclamations (quite in vogue for large development projects in Penang, Melaka and Johor).

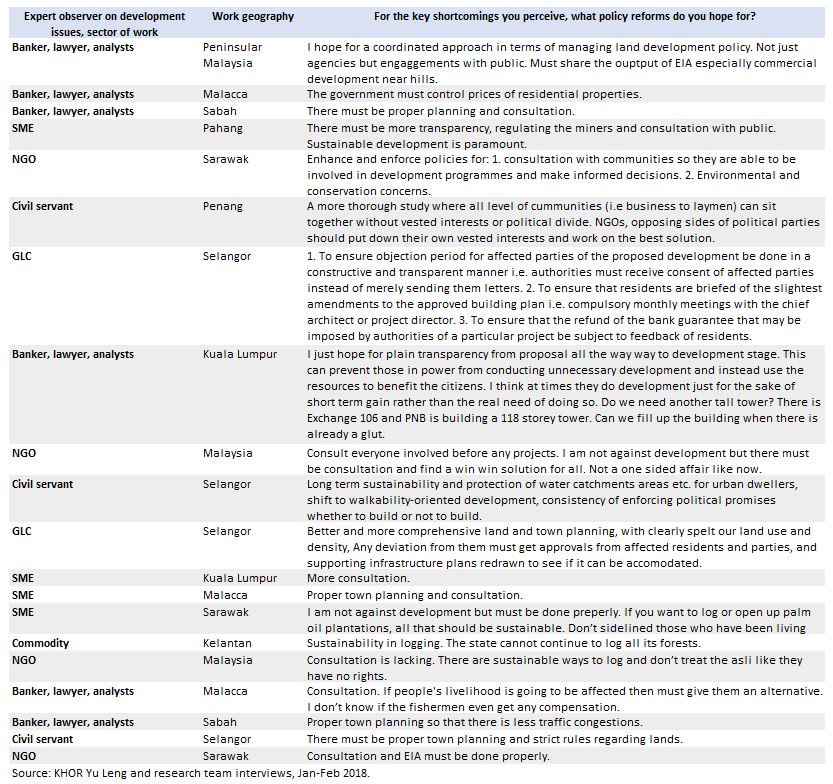

We spoke to 20 expert observers of land development issues (including three civil servants, whose views are featured in Appendix 1) with a semi-structured questionnaire. The key findings are shown in Table 1.a, and displays across-the-board concern about land governance, with a slightly positive view on economic outcomes, and strongly negative views on environmental and socio-economic impacts. Table 1.b presents observers views on policy reforms needed and indicates their economic sector and work geography.