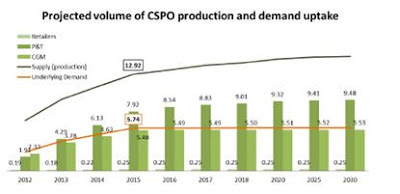

Back in 2010, Khor Reports first highlighted the

problem of a structural demand deficit at the RSPO. The latest supply and

demand forecast from the voluntary sustainability certification organisation

suggests that supply is set to continue exceeding demand by a factor of two for

the foreseeable future ie. market uptake for CSPO may remain at about 50

percent, even during the 2015-2030 period.

RSPO publishes key data from its members for the first

time

The RSPO requires that its members report on both their

progress and their future commitments on sustainability. In its “Annual

Communications of Progress” (ACOP) effort for 2011/12, the RSPO has made a good

effort to offer crucial insights into the future supply and demand for its

sustainability program. For the growers, this means they need to report

annually on key items such as planted area, new planting area, and third party

fresh fruit bunch (FFB) sourcing. For consumer goods manufacturers (CGMs) and

retailers, they need to report on volume of palm oil products sold in own-brand

products. Crucially, all have to report on their time-bound plan (TBP) or year

to achieve their respective 100% implementation of RSPO certification.

Future market uptake of CSPO may range 40-62%

By the RSPO’s reckoning, market uptake may only be 44%

in 2015, subsequently drifting down to 39% in 2020 and 38% in 2030. This

forecast is based on a relatively conservative “underlying demand” which

comprises commitments based on current usage by CGMs (includes key users of palm

oil such as Unilever and Nestle as well as big bio-diesel providers such as

Neste Oil) and retailers (including the likes of Wal-mart and Tesco, with

significant own-brand products businesses). For fear of double-counting, this

demand forecast excludes volumes from the processors and traders category

(whose members include Wilmar and Cargill), since they are supply-chain

providers to the aforementioned groups and no detailed information was sought

on volumes for their own end-product usage, which includes cooking oil and

animal feed.

Source: RSPO

On a more optimistic measure, based on commitments by

processors & traders, demand could rise to 7.92, 9.32 and 9.48 million MT

in 2015, 2020 and 2030; resulting in market uptake of about 62% for 2015

through 2030.

Taking the average of the more conservative and more

optimistic demand forecasts, the outlook is for 51% market uptake for the

period 2015 to 2030. Thus, the RSPO concludes in its October 2012 report that

“the current pattern of only about half of available CSPO being consumed may

persist unless more manufacturer and retailer members of the RSPO make

commitments to use it on the supply-side…. the RSPO needs to work harder to

increase the number of CGMs, including as yet non-members who are committing to

use CSPO as well as far harder at promoting CSPO amongst companies that are not

yet members. In particular, markets outside of Europe and the US need to start

demanding CSPO if the projected supply is going to be matched by demand.”

Structural oversupply

This lacklustre outlook is despite the good effort of

RSPO in rapidly expanding members in the CGM and retailer categories in the

last two years and pushing for 100 percent global procurements from them by

2015. The effort of the WWF's buyers’ scorecard (to pressure CGMs) has been

quite instrumental in this regard too. RSPO is the brainchild of the WWF.

The forecasted demand deficit therefore appears to be

a structural problem. We think it is a result of two factors.

First, the highly concentrated industry structure in the

global palm oil growing sector clearly exceeds that of the global CGM industry.

Unilever, with 1.3 million MT of palm oil usage each year, has played a key

lead role in the RSPO. Subsequently RSPO has signed on many others. It is hard

to think of a big global brand who is not a member. However, the commitments

from nearly all the big global brands are insufficient to mop up supply of RSPO

sustainable certificates from the growers. This sector is highly concentrated

with 85 percent global supply from Indonesia and Malaysia where very large

corporate growers have a big market share. In Indonesia alone, there are five

(5) groups whose individual annual production of palm oil are close to or

significantly exceed Unilever’s tonnage. Big growers are key contributors to

the RSPO. Small estates and smallholders have been left out of the

certification game (apparently unless receiving exceptionable financial and/or

non-financial support).

Second, the RSPO requires 100 percent of a grower’s

area to be certified. It is therefore designed to disregard market demand. This

is in contrast to the Roundtable on Sustainable Soy (RTRS), the certification

for soy, the key competitor of palm oil. Here, the WWF and Unilever also play

key roles. RTRS members, while having to abide by some key universal

principles, are free to decide how much of their area should be certified.

The RSPO

therefore faces the challenge of boosting demand for sustainable palm oil,

beyond the global brand names and in the face of "palm oil free" challenges

in its key EU market.