Palm oil is the lifeline of Malaysia’s economy. It is what puts the food on the table for many Malaysians, living in rural areas. Palm oil is versatile in its usage and it is found in many of the daily products we consume including confectioneries, biscuits, cosmetics, and detergents. However, the expansion of the palm oil industry, especially in Southeast Asia, has come under scrutiny because of its link with degradation of tropical forests as land is cleared for the development of plantations. It has been questioned on its contribution to climate change among other predicaments.

Therefore, it should come as no surprise that there is negative perception of palm oil in the European Union, Malaysia’s third largest importer of palm oil. Brussels is set to enforce a biofuel restriction, to take effect in 2020. This relates to the EU's renewable transport target, which uses palm oil as one of the feedstocks for biofuel, and seeks to remove deforestation impact. Unfortunately, there is worry about the livelihood of smallholders in the rural areas in Malaysia reliant on the export of palm oil. Some experts have also pointed out that the EU restriction (often confusing cited as a ban) may lead to the expanded cultivation of other (less efficient) vegetable oils. This could harm the environment in a manner comparable to worries about the cultivation of palm oil, if not, worse.

The Malaysian government, in an effort to bolster its palm oil economy (amid this uncertainty), has launched (in phases) the B20 biodiesel programme. It considers this a green fuel programme, and blends 20% palm methyl esters and 80% petroleum (up from the previous B7 blend), thus “increasing the country's palm oil consumption for domestic biodiesel industry rise to about 1.3 million tonnes annually”. The expanded local demand is meant to safeguard the sector and its stakeholders, especially its smallholders.

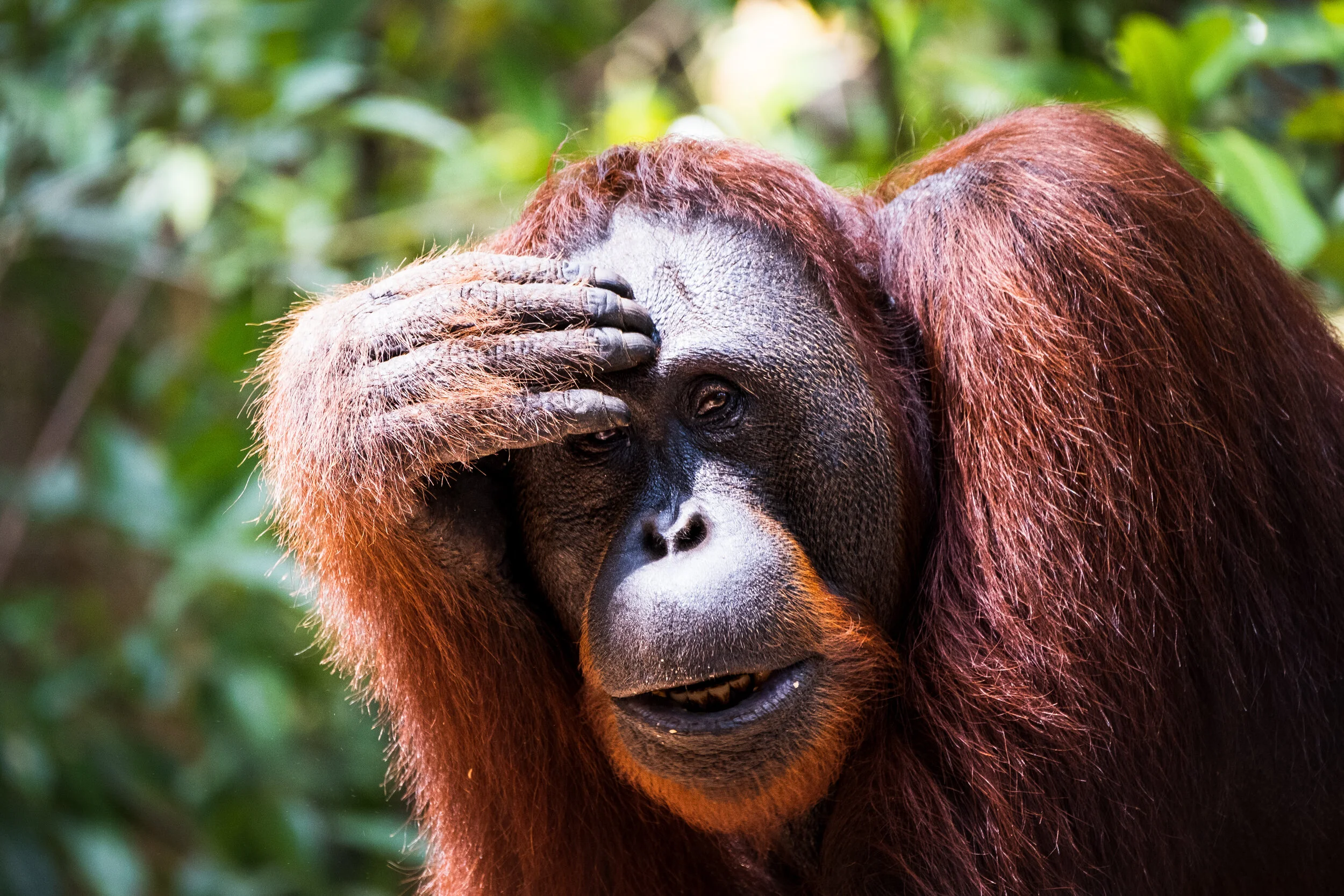

The cultivation of palm oil is going more sustainable, with research on best practices in the management of its estates and smallholdings, but misunderstandings still arise on conservation efforts - for the wildlife displaced when developing the forest to cultivate palm oil. On its website, The Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) appears to record palm oil’s (its) wildlife support activities under its Science Of Malaysian Palm Oil section. It initiated the Malaysian Palm Oil Wildlife Conservation Fund (MPOWCF) in 2006 (with a 1:1 top up offer for independent donor funds) to manage the various conservation projects in protecting and rescuing the animals that lost their homes to palm oil plantations. Its website (accessed 5th Nov 2020) lists 10 projects, but details about donor funds, project spending and impacts are not included.

The latest project is the Sabah Wildlife Conservation Colloquium 2012, and there appear to be two ongoing projects:

The Jungle Patrol Unit with Sabah Forestry Department to safeguard wildlife and deter poaching, 2007-ongoing; and

The Wildlife Rescue Centre with Sabah Wildlife Dept/ShangriLa Rasa Ria for Rescue & translocation of endangered wildlife found in oil palm landscapes, 2010-ongoing.

However, the latest reported Malaysia palm oil efforts, which is not listed on the MPOC’s wildlife page, includes the One Million Forestry Species Tree Planting Project in the Ulu Segama Malua Forest Reserve located in Lahad Datu, Sabah, a project announced in mid-2019.

In other news, the rise of green diesel in Indonesia, i.e. biofuel made entirely from palm oil worries, are not without its concerns; higher demand for green diesel means higher demand for palm oil, which for some experts translates to more environmental problems including loss of biodiversity and forest areas.

Additionally, then-Primary Industries Minister Teresa Kok also stated that the additional RM1 cess per tonne of palm oil produced would be collected and funnelled into a fund for green initiatives, which will then be utilised for wildlife conservation purposes and green initiatives, particularly for forest replanting.

MPOC has hosted talks, conferences and seminars about the sustainability of palm oil. Recently, it held a webinar on the 12th August 2020 in conjunction with World Elephant’s Day, with an overarching theme of ‘Human and Wildlife Co-existence: Turning Conflict into Co-existence’ focusing on human-wildlife coexistence within palm oil plantations and the conservation efforts in protecting the animals who have lost their homes. The panels consisted of Mr. Erik Meijaard (Chair of the IUCN Palm Oil Task Force), Mr. Vivek Menon (CEO of Wildlife Trust India), Dr. Senthilvel Nathan (Sabah Wildlife Department), and Mr. Izham Mustaffa (FELDA).

Aerial view of the Kinabatangan area in Sabah showing oil palm and partial river corridors. Full forest connectivity is crucial to allow wildlife to move through these multifunctional landscapes. Photo and caption credit by Marc Ancrenaz/Mongabay.

Mr. Meijaard discussed biodiversity conservation in oil palm landscapes and commented that it could be better. He explained that palm oil concession companies should set aside 60% of its landholdings for conservation efforts as done by PT KAL (in Indonesia); interestingly, he talked about conservation for orangutans as they are more likely to inhabit palm oil plantations, thereby substantiating the need for a conservation area to allow a ‘cohabitation’. He also questioned the effectiveness of translocating orangutans which involves rescuing, rehabilitating and releasing them back into the wild. What is needed is an effective biodiversity management.

Mr. Vivek Menon and Dr. Senthilvel Nathan approached human-wildlife coexistence, specifically between humans and elephants. Mr. Menon has put forth several strategies for coexistence between humans and elephants, including: (1) addressing habitat shrinkage and fragmentation by securing elephant corridors; (2) addressing and reducing human-elephant conflict through efforts such as voluntary relocation of families and smart infrastructure; and (3) raising the people’s tolerance for elephants.

Dr. Senthilvel Nathan spoke on the human-elephant conflict in Sabah. He noted that elephant deaths in Sabah are attributed to mainly hunting (ivory), accidental deaths (elephants falling into mud pools), and diseases (tuberculosis). There are wildlife management issues, lack of resources and poor coordination between NGOs, industry stakeholders, corporations, and the government; and a lack of general awareness, and poor understanding of several key scientific facts. He pointed to the Sabah State Bornean Elephant Action Plan (2020-2029) that was planned by the Sabah State government through the Elephant Task Force.

Bornean elephants feeding in an oil palm plantation. Photo and caption credit: Nurzahafarina Othman/Mongabay.

The last speaker, Mr. Izham Mustaffa spoke of human-wildlife coexistence from the industry’s perspective. He explained the effects of human-wildlife conflicts: plantations are damaged, palm oil trees were mostly uprooted or broken down. He referred to elephants wandering into the plantations looking for food, leading to standoffs between humans and elephants. The preventive actions taken by FELDA include electric fencing at the borders and translocations to forest-reserves. Mr. Izham suggested a few ways to coexist between humans and elephants: (1) increase awareness among stakeholders and settlers; (2) enriching wildlife habitat; (3) increase food availability in the forest reserve; and (4) establishment of wildlife corridors.

In a nutshell, the webinar was mainly about the conservation of biodiversity in palm oil plantations, which would be possible if all relevant stakeholders have a strong political and public willpower when managing palm oil plantations.

For more on the arguments put forth by the panelists about the importance of biodiversity conservation, just click here.

By Cyrene PERERA, Segi Enam intern, 17 Nov 2020 | LinkedIn

Edited by KHOR Yu Leng and Nadirah SHARIF