Segi Enam’s Khor Yu Leng was recently interviewed by BFM to comment on the new EU Non-Deforestation Regulation.

Listen to the full interview here.

Segi Enam’s Khor Yu Leng was recently interviewed by BFM to comment on the new EU Non-Deforestation Regulation.

Listen to the full interview here.

Last week, University Putra Malaysia’s Institute of Tropical Forestry and Forest Products (INTROP) collaborated with the French Agriculture Development Centre (CIRAD) and the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) to host a webinar on the geopolitical issues surrounding the palm oil industry and deforestation.

The speakers and panellists approached the subject matter from different perspectives: (1) Jean-Marc Roda spoke about a range of topics, including the regulation of imported deforestation, the ever-evolving issue of food security and consumption, and Europe’s biofuels conundrum; (2) Alain Rival explained palm oil’s vulnerability to climate change and the growing need for more sustainable agricultural systems within Southeast Asia region to address that vulnerability; and (3) Khor Yu Leng discussed social media attention on key commodities as well as recent developments relating to trade and climate governance.

Source: Roda, CIRAD/UPM (2021)

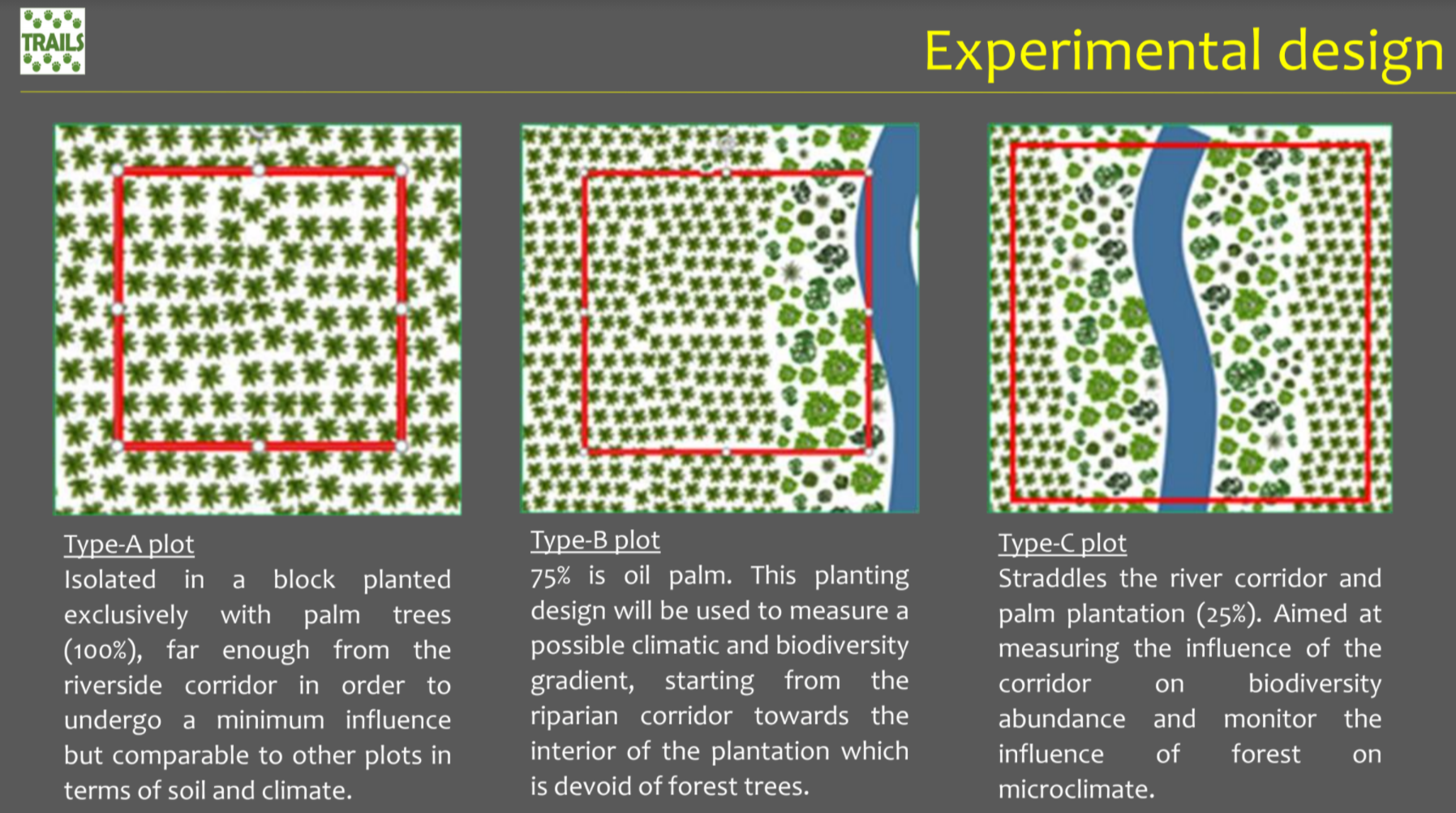

Source: Rival, CIRAD (2021). Experimental palm oil plots of TRAILS, a forest landscape conservation programme tackling the adverse impact of large-scale agricultural expansions on land cover change and biodiversity.

Source: Khor, Segi Enam (2021)

The Global Land Analysis and Discovery System, otherwise known as GLAD, is a popular tool that flags disturbances to the global forest canopy which may be due to deforestation. Developed by the University of Maryland’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery laboratory, the system relies on NASA’s Landsat satellite imageries and is mainly designed to provide law enforcement authorities, local communities, and the like near-real-time alerts of potential deforestation activity. An interactive map showcasing the alerts is available on Global Forest Watch.

A recent study by Maffette et al. (2021) has shown that the benefit GLAD has brought extends beyond its primary role as an alert system. The study, which analysed deforestation rates across 22 nations between 2011 and 2018—the last five years before and two years after GLAD was launched—indicated that GLAD has resulted in carbon sequestration benefits worth hundreds of millions of dollars in just the first two years of its use; in Africa alone, it is estimated that the social cost of carbon for avoided deforestation, i.e., the measure of economic harm due to carbon dioxide emissions, was worth between USD149-696 million within that same time period. Interestingly, according to Moffette:

“We think that we see an effect mainly in Africa due to two main reasons. One is because GLAD added more to efforts in Africa than on other continents, in the sense that there was already some evidence of countries using monitoring systems in countries like Indonesia and Peru. And Colombia and Venezuela, which are a large part of our sample, had significant political unrest during this period.”

Various NGOs have investigated and challenged the inclusion of mill suppliers who deforest; and there is controversy over suspending or engaging with errant suppliers. Wilmar says to avoid suspension contributing to “a growing leakage market” or negatively impacting oil palm smallholders, post-suspension engagement is crucial... to assist suppliers in bringing their operations to compliance.” Its “Suspend then Engage” grievance approach took effect in January 2019.

For human rights complaints, a supplier must take steps “to address the grievance with regard to the development and implementation of the time bound action plan which includes corrective actions, remediation actions and actions to demonstrate systemic and group-wide change.”

Under its “Re-engagement Protocol”, Wilmar may resume sourcing from suppliers suspended for deforestation and/or peatland development if re-entry criteria (specifying minimum terms and conditions) are met. An example is the so-called GAMA Group, apparently consolidated under KPN Plantation (and associated with Martua Sitorus, a Wilmar founder). Its recovery plan interventions centers on "social recovery, specifically supporting the development of hutan desa (community social forestry) programmes in the area to support community empowerment and improving livelihoods. The recovery plans also consider landscape recovery where feasible, such as creating wildlife corridors."

According to ‘Wilmar’s Supplier Monitoring Programme’ of Sep 2018 (the latest report, accessed 10 Dec 2020):

Suppliers report their current compliance to Wilmar’s NDPE policy via Its online self-reporting system and there is follow-up verification for 10% of mills. The verification programme included satellite monitoring of 11 million hectares and 500 mills by Sep 2018.

“16 suppliers (were suspended) at a group level, as they failed to convincingly improve their policies and/or actions, supply chain exclusion at a group level has been imposed,” and for Indonesia a million tonnes worth of supply has been suspended while about 1.2 million tonnes was under ongoing engagement. The total under complaint (suspension and engagement status) was 3 million tonnes of supply (including Malaysia and rest of the world). This tonnage under complaint is about 12% of Wilmar’s 25 million annual tonnes of palm products handled in 2019. The Indonesia complaints seen by Wilmar relate to about 5% of Indonesia’s palm oil production of about 43 million tonnes per year; and they likely appear as complaints for other Indonesia-based trader-processors too.

Editor’s note: Interestingly, Wilmar exited from the High Carbon Stock Approach in April 2020, citing governance and financial issues. The company, however, insisted that it “firmly committed to the adoption and implementation of the HCSA toolkit”. Wilmar’s press statement on its exit can be read here.

On 22 July, Chain Reaction Research (CRR) held a webinar to present their findings on a rather interesting subject matter: spot markets.

The spot market refers to one-off transactions that occur outside of long-term contracts, and are typically used by suppliers to get rid of surplus stock and buyers to plug shortfalls in capacity. This is antithesis of the usual business models of long-term contracts, and while transactions made via the spot market are estimated to be much fewer compared to the those long-term contracts, the spot market does pose some degree of risk to No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) compliance.

Here are a few key points and findings by CRR:

Unsurprisingly, there is little transparency by companies when it comes to disclosing information regarding spot market transactions. A good case study would be Sime Darby—between 2017 and 2020, seven non-compliant suppliers entered the company’s supply chain via spot purchases, one of which was PT Saraswati Utama, a company that was heavily linked to illegal deforestation. Sime Darby acknowledged the purchase, but maintained that since it was made on the spot market, it does not have any real link to PT Saraswati Utama.

Purchases made by companies on the spot market appears to be opportunistic in nature rather than a preferred business strategy. Genting and Sawit Sumbermas Sarana are two examples of companies that use the spot market but are currently adopting different business models. For suppliers, however, the spot market can be a viable business model, even if the purchases made are materially insignificant for the buyers. An example would be Palma Serasih, a company suspended from the NDPE market after being found to have cleared 6,500 ha of forestland in East Kalimantan between Jan 2016 and May 2020. In the first quarter of 2020, Palma Serasih’s biggest buyers were LDC and Sime Darby, with Sime Darby confirming that it made two spot purchases of insignificant material from Palma Serasih earlier in 2020.

CRR identifies spot markets as a threat to NDPE compliance due to: 1) the lack of transparency; 2) information on the supply base not being provided until after the purchase is made; 3) the nature of a one-off transaction negates the incentives for a supplier to comply with the NDPE; and 4) the limited incentives to commit to NDPE since companies can still generate enough revenue from spot market transactions alone, i.e. Palma Serasih.

On 2 July, Trase presented its Yearbook 2020, which aimed to address four key issues: 1) how is agricultural expansion linked to deforestation; 2) who is buying forest commodities and from where; 3) what are the greatest sources of deforestation risk in the supply chains of major commodity buyers; and 4) what is the coverage of zero-deforestation commitments and what impacts are they having.

During the launch, Trase presented the several interesting key findings:

Focusing on the Amazon, Cerrado, and Chaco where deforestation, Trace researchers confirmed a direct correlation between expansion of cattle pastures and soy, with cattle pastures being the dominant causes of deforestation across all three aforementioned areas in 2018, i.e. 95% in Paraguay, 81% in Chaco, and 54% in Cerrado.

Trase found that the market share of dominant trading companies is generally proportionate to their share of deforestation risk, although smaller traders can have disproportionate impacts as well.

Coverage of zero-deforestation commitments is increasing, although significant gaps remain in certain industries. Companies with the highest risk exposure per tonne often lack commitments, and at the moment, there is still no clear difference in risk exposure between committed and non-committed companies.

Source: Trase (2020)

We are hearing from the market that some feel that the proposed Malaysia "limit" to oil palm area is a signal for expansion! The area limit (first mooted at a lower level, then raised) has been suggested as a measure to improve the image of Malaysian palm oil against foreign accusations of deforestation. At the same time, it may ease palm's supply glut (resulting from rapid expansion when palm prices were buoyed in the biofuels boom).

Some figures may explain this alleged “pro expansion” mood. 6.5 million hectares is significantly higher than the current licensed area; and the implied pace of expansion would be 130,000 hectares per year for a push to the limit by 2023 (the “target” year mooted by the government, see red line in chart). This is a significantly faster pace than recent growth in hectarage (blue line) of 69,000 hectares per year in the recent 3 years.

But if there is an upward revision of planted area, of say 5%, the pace of expansion to reach the limit could be 80,000 hectares per year (yellow line; not so far off the recent 3-year average change).

How would the area expansion be distributed? Or perhaps 2023 is not a “target” year and upstream industry players are quite mistaken in interpreting it this way.

Read more at Palm Weekly!